|

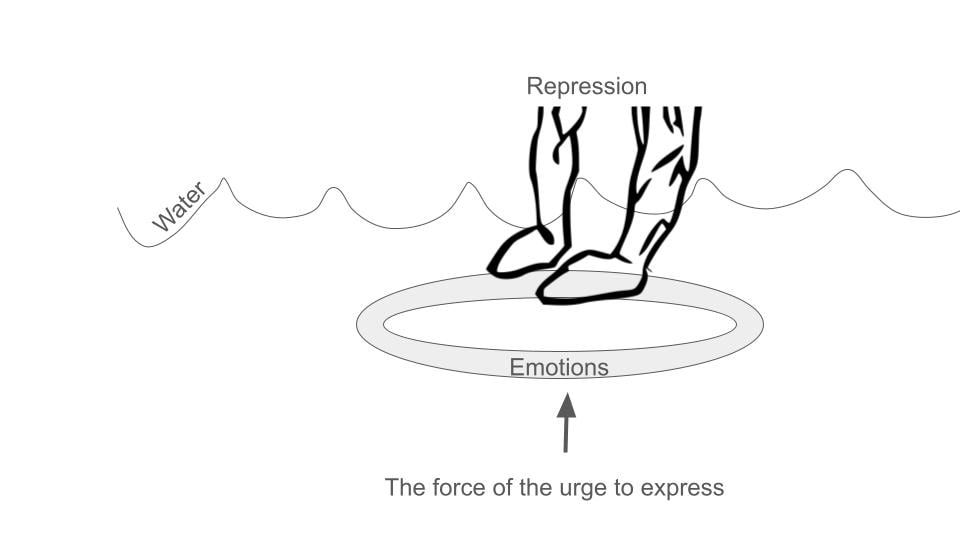

Expect Complex Emotions and Be Ready by Knowing Your Own Complexity Have you ever heard clients (or loved ones, if you’re not a therapist and want to participate in the exercise) say things like this? What are the underlying emotional states you see in each example? (Suggested answers are at the bottom of the article.) 1. “I just feel so much rage, I literally see red. Like my vision is covered in a red film.” She said, visibly shaking in her seat. “If my colleagues knew, I don’t know, I could lose my job, or worse, my reputation. I’ve done things I’m not proud of.” 2. “I’m bad…” he stares off into space, “evil. There’s evil in me. I feel like I deserve all the bad things that happened to me. It's hopeless; I’ll never get better.” he pauses again, “I dont know if I want to get better. I want to die and take the whole world with me. Burn it all to the ground, you know?” 3. “When I think about what happened,” they said grimacing, “I dunno,.. Ugh!” they stuck their tongue out as if to vomit and lifted their hands, repulsed “It's just so disgusting, it's unbelievable! I CANNOT believe it.” 4. “I think I hate him…I HATE HIM!” he exclaimed, suddenly stopping in his tracks like a record scratch. His eyes stared off to a corner in the room, and all the life drained from his face. His voice faintly floated out of his throat, saying, “Oh wow, I was so worked up, but now I have no idea what we were talking about.” In the world of therapy, emotions are complex and varied, often bringing forth a rollercoaster of feelings for clients. As a therapist, it's crucial to expect and embrace the full spectrum of emotions that clients may experience during sessions. Here, I will explore the importance of acknowledging and creating space for feelings such as shame, anger, sadness, vulnerability, confusion, disgust, and even suicidal ideation. We'll discuss why attempting to "fix," "soothe," or "dismiss" these emotions is counterproductive and explore the role of dissociation in emotional processing. Moreover, we'll discuss practical strategies for therapists to navigate intense feelings, incorporating somatics and parts work into the therapeutic process. Embracing a Range of Emotions: Clients seeking therapy may experience a wide array of emotions that are often considered uncomfortable or challenging. It's essential for therapists to anticipate and acknowledge feelings of shame, anger, sadness, vulnerability, confusion, disgust, and even thoughts of suicide. By expecting these emotions, therapists can create a safe and non-judgmental space for clients to explore and express themselves. As you practice, you will start to recognize the “aesthetic” of an emotional state. The aesthetic is a multifaceted experience of the person that includes thoughts, emotions, sensations, postures, movements, body tension and collapse patterns, images in the client's and therapist's minds, and more. Sometimes people refer to the aesthetic as the "energy" or "vibe." The ability to recognize the aesthetic enables you to determine what emotional state is present faster and to validate the client experience more fully. For example, I can reflect that a client is sad because they are tearful. If I have a more complex relationship with aesthetic and I am attuned to the overall aesthetic of "sadness" in this person, I can reflect a shift to sadness before the client is fully in it, which increases rapport and trust in that the client feels acutely tracked and also feels “felt.” Furthermore, not all clients cry when sad. Acknowledging sadness when the client's expression might be more subtle, or the person’s sadness is generally not recognized or honored, can increase the client's awareness of sadness and help the client feel safe to feel the sadness now and increasingly as time goes on. This goes for any emotion, especially socially “inappropriate” ones. Thus, we heal the consequences of death by a thousand paper cuts that shove emotions down underwater. Many people have not been explicitly told to “not feel that feeling” but have gleaned from their environment that it is not okay to feel certain feelings. This is primarily done through dismissing, fixing, and soothing. The result is like trying to hold a life raft underwater: Avoiding the Urge to Fix or Dismiss: The impulsive reaction for many therapists, like those who trained the client not to feel in the first place, might be to alleviate their clients' discomfort by attempting to fix, soothe, or distract them from their emotions. However, these well-intentioned efforts can hinder the therapeutic process. Therapists should resist the urge to "fix" and focus on naming, validating, and feeling along with the emotions the client is experiencing. The exception to this rule is when a client dissociates; I will address that later. The reason that I see therapists have a hard time with this is that therapists have discomfort with their own socially unacceptable emotions. The only way for a therapist to get really good at validation is to be willing to feel fear, shame, disgust, and even suicidal ideation. The therapist needs to be unafraid to feel these feelings. Are you afraid to feel fear, sadness, loneliness, hopelessness, and the inner condition that causes suicidal ideation? If so, that means you don’t trust yourself to go into the emotional state and then come out of it. Another way to say this is that you don’t know how to regulate your nervous system at that level. Nervous system or emotional regulation does not mean that you are always serene and placid. It means that you can go into ANY feeling and efficiently find your way out. Ideally, what happens is the therapist feels a little bit of their version of the client's feeling, like rage, for example. Here’s how it goes down: The client looks tight; their jaw is clenched, biceps flexed, shoulder rounded forward, fists are starting to ball up, and their brow is furrowed as they talk about how, once again, their partner is making unreasonable, selfish demands. You say, “Wow! A lot of rage, huh?” Client: “Oh…my…god, I could punch a wall right now.” Therapist: “Oh yeah! Anyone would feel that way. I’m angry too hearing about this. Is it okay with you to feel this anger right now?” Client: “Yes, but I feel so stupid getting charged up like this.” Therapist: “Sure, that makes sense, you were taught it's not ok to be angry.” Client: “Right, anger was off limits. Mine was, anyway. What's the point of this anger anyway? It doesn't fix anything.” Therapist: “It's really uncomfortable to feel that much anger, huh?” Client: “Yeah, what do I do now?” Therapist:” What does your anger want you to know?” Client: “I am lonely and hurting.” Therapist: Oh yeah, can we just feel that loneliness and hurt together? Client: “Yes, that’s ok.” Therapist: “What’s it like to have someone feel this loneliness with you?” Client: “It's nice.” Therapist: “What's nice about it?” Client: “I do not feel alone; my anger can calm down. I feel like I can see my relationship in a different way.” This is an abbreviated example of validating, joining, and connecting the dots for the client and inviting the message of the feeling. There are many ways that this example does not capture how complex a dialogue like this can be, but the overall flow and format I present is something I experience repeatedly in sessions. Feelings are messengers. If we told the client to “try some deep breaths” when they wanted to punch the wall, we might not have arrived at the vulnerable feelings underneath. and we would not have been able to help the client feel connected. Notice how when the client feels connected and regulated, they can reframe their situation on their own. The therapist did not have to give them advice. This is the power of good implicit and explicit reflection statements, validation, and feeling with the client. It winds up being a lot less work for the therapist. Many therapists burn out, even in private practice, because they think they need to know everything or at least know a lot. Interpretive knowledge can help you steer the ship, but in actuality, you just need to know how to follow the client. That kind of knowledge is much less “expensive” than having to figure out how to interpret everything all the time. Understanding Dissociation: Many clients have learned that their feelings are not acceptable or valid, leading to dissociation as a coping mechanism. Therapists need to be vigilant for signs of dissociation, as it can be damaging if left unaddressed. Monitoring for dissociation and understanding its nuances is crucial for effective therapy. Rather than reacting to dissociation with panic or discomfort, therapists should strive to become competent and confident in handling it. Signs of possible dissociation include client reports and visible clues. Clients might report feeling confused, foggy, or suddenly feeling blocked while processing. Clients might not have words for what they are feeling, but you will get the hint they are dissociating because they suddenly look scared, frozen, or far away. Their speech may become slower, and more disorganized, their sentences might seem incomplete, or they may change subjects rapidly, becoming difficult to understand. It is important to know how to name the dissociation respectfully and artfully bring it to the client's attention. When a client dissociates, it means that something just “happened,” usually something that is “intolerable” for their system. Reassure the client that they always have consent and dont have to feel something they don’t want or aren't ready to feel. This reassurance can take the pressure off of the dissociation. I usually ask the client, “What was intolerable about what we were talking about just now?” Usually, the answer has something to do with “I’m not supposed to feel ______,” “I’ve trained myself not to feel_________,” “It’s too vulnerable to feel________,” etc. Rarely does a client recall a memory of which they weren't aware. Rather, it's usually an emotion or sensation that the client trained themselves not to feel long ago. Titrating Intensity with Somatics and Parts Work: To ensure the emotional intensity remains tolerable for clients, therapists can integrate somatic techniques and parts work into their practice. Somatics involves paying attention to the body's physical sensations, helping clients ground themselves in the present moment. Parts' work explores the various aspects of a client's personality or identity, facilitating a deeper understanding of their emotions without being consumed by them. The work, then, is to help the client learn to tolerate what has previously been intolerable. My aim with clients (and myself) is to be able to be present with any emotion or sensation. Once someone no longer has “off-limit” feelings, they experience much greater ease, clarity, and flexibility in life. It’s much easier to be continuously present. They can feel a feeling and efficiently find their way back to a healthy baseline, which is much easier to achieve if the therapist is constantly modeling regulation this way. It's a simple goal arrived at by a varied and nuanced path for every individual: Therapists play a vital role in helping clients navigate complex and challenging emotions. By expecting and embracing feelings of shame, anger, sadness, vulnerability, confusion, disgust, and suicidal ideation, therapists can create a supportive environment for clients to explore and express themselves. Avoiding the temptation to fix or dismiss these emotions, monitoring for dissociation, and incorporating somatics and parts work are essential strategies for therapists to foster a more profound and effective therapeutic journey for their clients.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Details

AuthorProsopon Therapy Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed